Market report

Painter insights

Uncover the dynamics of Europe's painter-dominated market landscape. Learn about the trends and challenges influencing artists and the broader art community.

Blogs I published 03 October 2025 I Dirk Hoogenboom

Small Players, Big Impact – Understanding Europe’s Painter-Dominated Market Landscape

Walk down a street in Madrid, Antwerp or Lyon and look at who’s painting the shutters, sanding the frames or rolling out new coats in the stairwell. It’s not a multinational with a dozen branded vans parked outside. More often than not, it’s one person with their tools in the back of a hatchback, a father-son operation or a crew of four who’ve worked together for years. That’s not circumstantial. That’s Europe’s painting trade.

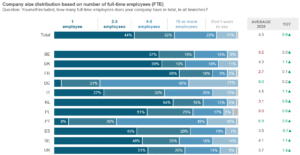

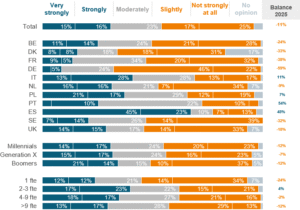

Our latest Painter Insight Monitor shows that the European painting industry is dominated by solo painters and very small companies. Mid-sized firms exist and show regional strength, but large companies with ten or more employees are rare. It’s a fragmented, localized and highly specialized trade built around small, flexible players.

This layout has advantages – agility, local trust, lower overheads – but it comes with its cracks too. Small firms carry the market, but they’re carrying it on older shoulders. The average painter is about 49 years old, and not enough younger hands are coming in. Renovation work keeps everyone busy, but labor shortages bite harder each year.

On top of that, most of the work is residential and renovation-focused. Painters spend their days refreshing homes, upgrading façades and keeping interiors looking sharp. New build projects make up only a minority of their workload. This makes sense when you think about Europe’s mature housing stock; there are more old walls to repaint than new ones to prime.

So, let’s look at the structure of the painting industry bottom up: who the players are, what kind of work dominates, where the workforce is headed and, most importantly, what it means for anyone working the trade.

A Market Built on Solo Painters

The data confirms what everyone in the industry sees on the ground – solo painters are the backbone of the European market. In most countries, more than half of painting businesses are run by a single individual. Meaning? These are the tradesmen who know their neighborhoods, keep loyal client lists and live off word-of-mouth. They don’t advertise much, they don’t have big admin operations, but still keep houses, schools and offices painted year after year.

Mid-sized companies (2–9 painters) play an important role too, especially in markets like Germany and France, where regional firms have built a reputation for reliability on medium-scale projects. These businesses often juggle multiple renovation jobs at once, sometimes dipping into small commercial projects. But large companies (large being 10+ employees)? They’re scarce. You’ll see them on large-scale new build projects or in niche commercial painting, but in the big picture they’re outliers.

Don’t expect consolidation in painting like you see in other trades. The economics and client dynamics keep the market small and local.

Why so many small players?

Low barriers to entry

Unlike HVAC or electrical trades, painting doesn’t require heavy machinery or expensive licenses. A van, ladders, rollers and some skill are enough to get going.

Localized demand

Renovation jobs are hyper-local because homeowners prefer to hire someone nearby. That keeps businesses small and close to home.

Trust and reputation

For a homeowner, trusting “the local guy” who painted a neighbor’s house is easier than calling a national chain.

Renovation vs. New Build

Talk to painters and they’ll tell you most of their work is fixing up old walls, not prepping new ones. That’s because in Europe, renovation eats up the majority of painting hours. New build projects do attract larger firms, especially those with enough manpower to handle the scale and deadlines of construction sites. But the bread and butter of the European painting industry is driven by homeowners, landlords and small-scale commercial clients.

Renovation work also shapes cashflow. Projects are smaller, often paid by private clients and come with quirks (a client changes paint mid-job, weather stalls an exterior or cash payment comes late). That’s why most painters stack small, reliable renovation jobs rather than gamble on one big new build contract that ties them up for months.

It’s simple economics. The continent’s building stock is old, and new build rates are slow compared to demand, unlike Asia or Africa. There are always apartments needing fresh coats, façades that need refreshing, windows that need sanding and repainting. Renovation is steady, cyclical, repeatable work – it’s what keeps solo painters booked out months in advance. Why?

Small firms = renovation

A two-man crew in Europe survives on kitchens, living rooms and stairwells. They don’t have the capacity to chase big contracts, but they don’t really need to.

Bigger firms = new build

The few companies with 15+ employees tend to show up on new housing estates or municipal jobs, where bigger teams are required.

Example

A solo painter in Portugal might spend most of the year repainting villas and apartments for homeowners. In contrast, a larger German company with 15 employees might secure contracts for new residential blocks or municipal buildings. Both are painters, but their day-to-day looks completely different.

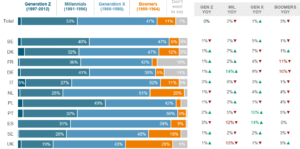

The Generational Gap – A Workforce Getting Older

Here’s an uncomfortable truth. The average European painter is nearly 50 years old. In some countries, even higher. Shoulders ache, knees give out and backs don’t forgive like they used to. That alone wouldn’t be alarming if younger generations were entering the trade in sufficient numbers. But they’re not.

The generational story looks more like this. On paper, the share of Gen-Y painters is increasing. But that doesn’t mean there’s a wave of Millennials flooding into the trade. What’s really happening is a generational transition. Baby Boomers are gradually retiring, and when they exit, the makeup shifts automatically toward younger groups. The pool itself isn’t growing; it’s just being reshuffled.

So yes, the average age is dipping a little. But that’s not because more young people are joining, but because older workers are leaving. Gen-Y painters now make up a larger slice of the pie in places as “leftovers,” but the reality is that Gen-X still dominates. The workforce could be called “stable,” but that only accounts for inflows roughly matching outflows. But stability here means stagnation, not growth. One painter retires, one enters. Net zero.

The implications are big:

- Boomers are retiring, taking decades of experience and often whole client networks with them.

- Gen-X is the current backbone, but they’re already in their mid-40s to late 50s. That means the next outflow is incoming.

- Gen-Y and Gen-Z aren’t joining in sufficient numbers to offset the gap. The “younger” workforce is only younger by comparison, not by true replenishment.

For painters running small businesses, succession is a real issue. If you don’t have an apprentice lined up, the company may close when you retire.

Labor Shortages a Critical Concern

The generational issue links directly to a broader labor shortage. When 64% of painting companies across Europe call labor shortage a critical concern, it’s not an HR soundbite – it’s a lived reality. Jobs take longer, clients wait longer and companies are forced to turn down work.

- Solo painters feel it in terms of their own limits. They’re used to working alone, but as they age, physical capacity becomes the bottleneck.

- Mid-sized firms feel it most. They need reliable crews to handle multiple jobs, but they can’t always recruit or retain, and generally can’t compete on wages against general contractors or other sectors.

- Large firms have more resources to recruit, but there are so few of them that they don’t change the market picture.

Labor shortages also show regional variation. Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal) reports the heaviest strain. Germany, despite its aging population, reports relatively less impact, thanks to better vocational systems and migrant labor.

External context:

FIEC (the European Construction Industry Federation) consistently ranks labor shortage as one of the top three challenges in construction. Eurostat reports that 40% of the EU’s construction workforce is over 50, and less than 15% is under 30. That imbalance shows why painters feel squeezed.

Why Fragmentation Cuts Both Ways

The painting market’s structure is paradoxical in nature – its strength is its core weakness.

Strength

Small firms are agile. They can pivot quickly, manage low overhead and survive economic shocks. If one client cancels, they find another.

Weakness

Fragmentation limits investment. Few firms have the scale to adopt new technologies, run training programs or market aggressively. When solo painters retire, their skills and client base often disappear.

This explains why the industry feels stable but fragile. On the surface, jobs keep getting done. But underneath, the system relies heavily on aging individuals with no clear replacements.

Practical Implications for the Industry

For those working in or with the painting trade, here’s what this landscape means in practice:

- If you’re a solo painter, think about succession early. Train an apprentice, bring in a younger partner or explore ways to extend your career with lighter, more ergonomic tools.

- If you run a mid-sized firm, labor management is your number one issue. Build relationships with vocational schools, consider offering formal apprenticeships, and invest in retention.

- If you’re a supplier or manufacturer, understand that most of your market is made of very small firms. Tools, paints and solutions that save time or reduce fatigue will resonate. Don’t expect most firms to adopt complex systems or digital platforms.

- If you’re a policymaker, support for vocational training and apprenticeships is crucial. Otherwise, the workforce erosion will accelerate.

Conclusion

The European painting industry is a story of small players making a big impact. Solo painters and micro-companies dominate the market, renovation keeps the demand steady and specialization keeps skills sharp. But beneath a perceived stability lies an acute fragility – an aging workforce, limited new entrants and chronic labor shortages.

The industry won’t collapse tomorrow – it’s too essential and demand for renovation will never vanish. But without a pipeline of younger painters and better support for small firms, capacity will slowly erode.

The lesson is clear. If you’re in the trade, don’t think only about the next job. Think about the next decade. How are you adapting to shortages? How can you keep delivering value when the labor pool keeps shrinking? And who’s replacing you?

Because for now, Europe’s painting industry proves one thing beyond doubt – small players carry a heavy load. The question is how long they can persevere..